In Bela Bartok’s Free Variations from Mikrokosmos Volume VI, Bartok writes a very modernist sounding piece that is defined by the constant repetition of minor seconds as well as the movement to and from tritones. The intervallic language of the piece does not give away the clear tonality that is represented when we listen to it, (though it does give hints) but nonetheless, the work sets up a system with a clear functioning tonic. Bartok uses this to his advantage when highlighting the old classical form of a theme and variations, which he is giving his own take on.

The first issue that must be addressed when asking how Bartok uses his own brand of tonal language to clarify form, is specifically how he creates this tonality. The way that most people think about a tonal system is the functional tonality that we are acquainted with in the baroque through the late romantic periods where a hierarchy of pitches is created through scales and voice leading. This idea of tonal harmony and tonality, though, is not a complete definition, as composers and theorists over the years have shown that there are other means to invent a tonic center or resting place.

As an example, another way to create a tonal center would be repetition, so that the listener associates everything to the repeated pitch. This though, is not how Bartok creates his tonality. He, quite like functional tonality, creates a hierarchy of notes that surround a central “tonic” pitch, departing and arriving on it. He particularly surrounds his tonic centers symmetrically.

Along with the central tonal pitch of A, which is considered the tonic of the entire piece, Bartok also implies different tonics for different sections. This helps clarify how he is organizing his own brand of tonality into this old classical form as I said before.

Bartok delineates his variations fairly clearly. He uses motivic rhetoric as well as harmonic language to make it clear when he has shifted into a different variation. As in the classical theme and variation form, there are eight variations that are arranged in a sonata form. The measures that encompass each variation follow:

Variation I: mm 1-12

Variation II: mm 13-23

Variation III: mm 24-33

Variation IV: mm 34-42

Variation V: mm 43-51

Variation VI: mm 52-64

Variation VII: mm 65-72

Variation VIII: mm 73-82

The first variation would be considered the beginning of the exposition, with the first theme clearly demarcated. Variation II would be the second theme in the exposition. Variation III would begin the development in the sonata form. The development would continue all of the way through to variation VI, where the retransition begins. Variation VII begins the recapitulation with a combination of theme one and two and variation VIII is the coda.

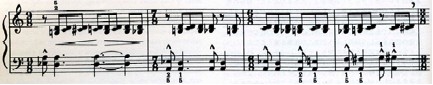

In the first variation Bartok gives us a run down on the harmonic language he will be using, the scale and important intervals. Bartok selects pitches from the octatonic scale of the pitch class (89E02356). The pitches he chooses outline a tritone, which forms the subset (235689) [see figure 1 below].

{fig. 1}

He uses this subset exclusively from bar one through the first quarter note in bar seven. The tritone is important in this work as it represents a critical interval for modulation, interesting pivots on axis, and a principle direction that the pitch-class moves towards other than the original minor second. The use of pitch motion to and from the interval of a tritone furthers the idea of its importance.

What isn’t clear from this snippet of the piece is whether G#, or A is tonic of the piece. It seems from this small area that G# is playing the role of the tonic as that is where Bartok departs from, and arrives back at via the octatonic scale. So, for the first variation, though the tonic of the piece, A, may be present, G# is actually playing a tonic in this microcosm (no pun intended) of the piece.

Bartok quickly dashes this G# world, as in measure seven he expands beyond the tritone limit he stuck to for the first six bars and lands squarely on a D and an A. This perfect fifth is a very stark contrast from the previous bars, but not to let the listener settle on D as being the tonic (which we are inclined to do as it is an arrival on the lowest pitch of an interval that is very stable to our ears), he throws this bizarre, upper register Bb, G#, A cluster into the mix [fig 2 below]. This is important, as it introduces the second theme’s “central” pitch, which is the Bb as well as the idea of the Major 7th, which recurs later on in the piece.

{Fig.2}

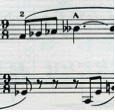

Bartok, does not stop with that simple introduction of the second theme’s tonic center. Instead, he moves the harmonic language of the work from the wholly octatonic, to the wholly chromatic [Fig. 3]. This functions as a transition area, much like you would see in a sonata between the first and second themes, where there is likely to be a modulation.

{Fig. 3}

After Bartok has strayed into this wholly chromatic, transitional area, he separates out between the two hands into two independent octatonic subsets [Fig. 4].

{Fig. 4}

He uses this chromatic area to launch the listener into the pitch area of the new octatonic subset, of which Bb is the “tonic” (note that the A still sticks around as the tonal center of the piece). Like in the first variation with the G#, Bartok departs and returns to that Bb over an octatonic subset covering a tritone.

Also, like in the first variation, he expands the tritone further to a perfect fifth when he is looking to begin transitioning to the next variation. Unlike in the first variation, he expands his moving line upwards in the right hand so that the perfect fifth is that of A and E [Figure 5]. It shows Bartok’s thinking of how he is demonstrating that A is the tonal center, by using it as an axis and expanding out from it to a perfect fifth. He also cleverly keeps the listener from settling on anything else as the tonic with the aforementioned leap to Bb, G# and A when he landed on the D, A Perfect fifth. Bartok, then, once again, strays into the wholly chromatic as if modulating before moving on to the next variation.

{Fig. 5}

In the next variation Bartok mixes up the placement of two pitch class sets so that the intervallic content seems more complicated than it really is [Figure 6]. This complicated harmonic language starts off the development section.

{Fig. 7}

Though the organization of the pitches may seem strange, it is really just two interlocking sets of pitches based on the two principle sets that defined the first two themes. These are G#, A and A, Bb. The C# and C are just products of Bartok’s wholly chromatic expansion to a major seventh in measure twenty-three, as well as being included in the G# or Bb based octatonic subsets. Hashing the sets of pitches out, G#,A and C form the same intervallic content as A, Bb, C# of (014).

In variation IV, Bartok uses the A as an axis again, but in each hand departs in a different direction. In the right hand it departs up the octatonic subset of (T013), and including the A, which is repeated, forms the ever-present tritone idea of (9T013). The exact inversion plays itself out in the left hand, being (35689). Bartok makes it clear in this variation that the A is central in its role as an axis [figure 7].

{Fig. 7}

Bartok does muck up what should be a clean inversion though, by changing the right hand just before it is about to land back on the A and Bb. He instead lands on a B natural before heading back up towards and E natural, which is just an extension of the octatonic subset that we have been dealing with. What this B seems to be doing there is extending the left hand’s own octatonic subset to that of a perfect fifth, just like the E natural is doing in measures 35, 37 or 38. In other words, it belongs in the left hand rather than the right as far as its placement in the individual octatonic subsets.

In variation V, Bartok really begins to make the tonal center of the piece unclear. Before, Bartok would be fairly precise as to where the tonic center is, by having it (A) be the center of a symmetrical cluster (as seen before, usually an octatonic subset).

Instead, Bartok initially creates the pitch class of E, A, Bb and Eb [Figure 8]. These are interlocked tritones, playing on one of the work’s principle ideas.

{Fig. 8}

Here, the center of this “axis” tonality is A and Bb. Bartok quickly makes things ambiguous, though, by throwing in a G# making the central cluster comprise of G#, A and Bb [Figure 9] (this cluster plays a large role in the piece, see measure 17 for an example).

{Fig. 9}

This seems to reassert A as the center, but for the first time, creates a truly asymmetrical figure around the A with E, G#,A Bb, and Eb. This lends to the ambiguity of the tonal center, with neither the A nor the interlocking tritone figure for which A and Bb is the center, asserting a tonic role.

The last eighth notes before the next variation further skew what the tonic maybe. Bartok uses interlocking fifths of Bb, F and C#, G#, centered around the tonic A, which calls us back to Bartok’s use (although spurious) of the 5th to highlight when he is modulating [Figure 10].

{Fig. 10}

This is the important reason for the complex shifting of “centers” and “axis”, as Bartok is making his modulation into the retransition, which is in the dominant key. The dominant key is not the traditional dominant of A (which is E), but rather Eb. This plays directly into Bartok’s recurring idea of the tritone as the principle interval in the work.

Variation VI begins the dominant section and the retransition of the work into the recapitulation. Once again, Bartok uses a subset of the octatonic scale to create a motion to and from the “tonic” of the section, Eb. In the right hand this is clear in the first bar (measure 52) of the variation. In the second bar he overshoots, seeming to settle on D, but this can be considered more of as a lower neighbor note. On a side note, the right hand in the bar outlines the principle interval of the work, the tritone.

The following bar is what leads one to conclude that Bartok is still in “Eb”. He notates a B double-flat instead of an A to clarify that the motion of the scale he is using is not towards the original tonic of the work, but to more of a dominant of the dominant [Figure 11].

{Fig. 11}

Skipping to bar fifty-six, Bartok begins his motion from Eb back to A. Since Eb and A are part of the same octatonic scale that he is using, he adeptly just switches hands with the theme of the particular variation, moving away from the tritone and seventh leaps in the left hand to an exact copy of the right hand in measure fifty-two, but in the key of A. Bartok plays out the transposition of the original phrase in the left hand and then continues on to the recapitulation, ending the development section.

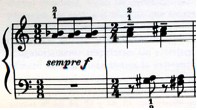

Variation VII looks to be a combination of the first two themes of the work, it is a return to the original theme of repetitive eighth notes spread between the two hands. This time, though, he wastes no time in combining the two octatonic subsets surrounding the tonic A. In bar seventy-two he expands out to the interval of a perfect fifth, this is important as it is and arrival point to which the variation was headed, and important to the final variation [Figure 12].

{Fig. 12}

The final variation plays on the meandering that has been demonstrated throughout the entirety of the piece, moving from and too the tonics of each section, or of the entire piece. The perfect fifth, as stated before is important, because it represents the largest interval in the section (except for a lonely F in bar 74), which slowly shrinks away into just the tonic without any other pitch played simultaneously. This occurs in the final bar. Bartok maintains the integrity of his A as an axis idea by having an E above it and a D below it in the first measure of the variation [Figure 13].

{Fig. 13}

This coda is fairly different from the rest of the piece, because instead of being mostly from an octatonic subset, it is almost wholly chromatic (usually it was the other way around). This seems to turn a microstructure from before (that wholly chromatic modulation that occurred in bars 7-12, or 19-23) into a macrostructure, that deserved it’s own presence in the piece. This all occurs just before the final arrival, much like the chromatic transitional sections were used before moving into a new section.

As can be seen from Bartok’s interesting modulations and assertions of where the tonal center is, he is just playing with an old form in a wholly new harmonic and intervallic language. The clarity and brevity with which he achieves this is astonishing and demonstrates knowledge for old forms and creativity in new musical languages, which are to be frank, enviable.