Our Interview with Cadillac Moon Ensemble and Jackson Parodi on WVUM 90.5 FM The Voice‘s classical lunch will air at 11:00AM EST Today! Topics discussed cover collaborating during the composition process, new classical music and much, much more! Oh, yeah also clips of pieces we’ve written for Cadillac Moon! Tune in here: http://wvum.org/index.php/wvum/stream/

I’m combing my way through Krenek’s set of essays Exploring Music, and it’s providing some great insight into the man and his beliefs. His vignette on Milhaud that I wrote about before was really cool. I’m currently digesting ‘New Humanity and Old Objectivity’ and some of his views on vernacular forms of art (pop music in this case) are astonishingly backwards. The genre or medium of a work should not be taken as a way to blanket judgement of quality. I turn it over to Krenek to show you what I mean:

Now in music the age has found the art that satisfies all its needs–popular music. As far as its production and consumption are concerned it corresponds perfectly to the other present-day principles of creation and running. Production takes on a conveyor-belt system–wach of the numerous operatives taking part in the process carries out only one ‘repeated, thoroughly leaned action’ as they say in the collective contracts for a given category of industrial workers. We hear that there are refrain-specialists, verse-specialists, specialists in harmonizing the half-finished product, others specially skilled in producing witty or imposing titles; there are others who do the rhymes and specialists in radio, salon, jazz and other orchestration who then put the finished project into its normal commercial package. It is rather like a cloth factory where at one end the wool is taken off the sheep and at the other the finished material emerges. But in this case the part of the fleeced lamb is played by the unconscious consumer.

This art is, of course, adjusted to the conditions of a large turnover; the goods are mass-produced, so that production costs are lowered the articles are almost interchangeable types so that you can get away with an unsubtle, dull feeling for the type and are not disturbed or surprised by individual traits; the material is easy to understand and the words satisfy the hunger for scraps of information in a particularly accessible field half-way between sex and sentiment.

But of course it must not be thought that this art is deliberately produced because there is a need for it, and that its creators could write differently if they chose. On the contrary, here as elsewhere the demand is created by the producers, for at bottom the public is indiscriminate, ready for anything. The writers cannot do anything else because they themselves cannot rise above this sphere and one cannot but be convinced that they are doing the best they can, for no artist can deliberately write below his real level. If anybody says he could just as well write symphonies as pop songs and only writes the songs because they pay better, he is lying, perhaps unconsciously, and ruining his character without improving his talent.

Seething through this passage is condescension for writers of pop songs, and popular forms themselves. Krenek states that, “if anybody says he could just as well write symphonies as pop songs and only writes the songs because they pay better, he is lying,” but is the inverse true at all? Could Krenek have written a single song out of Exile on Mainstreet? Additionally, the idea that multiple parties coming together to produce a musical track “fleeces the unconscious consumer” is utterly false. Does the help Al Green, The Supremes, Beyoncé, and so many more artists receive over the course of producing their albums inherently reduce the value of their music? There is remarkable depth to some popular songs, this is not a new idea.

Couldn’t write a symphony.

I’ve got a bunch more to input, but it’s coming along.

His house, filled with old-fashioned furniture and family photographs by suburban photographers, is a kind of chamber of horrors, the exhibits being fantastic, tasteless objects from every chance country — particularly bottles, which Milhaud collects with a rare passion and success. He is also madly in love with his old picture postcards showing highly varnished couples in front of twilit pools with flat backgrounds, or idiotically smirking pink ladies saying ‘Ne m’oubliez pas!’ and similar abominations from the lumber-room of the nineteenth century. It is no love-hate that binds him to these things, no surrealistic feeling of horror at the deadness of this aesthetic world, but the primitive southerner’s honest fondness for the highly coloured, absurd clichés which give pleasure to simple-hearted sailors and housemaids. A gin bottle shaped like and umbrella may be objectionable aesthetically… This throws a light back on Milhaud’s work, so far removed from all artiness, and always taking the most direct route to the heart of its subjects and so to the hearts of its listeners. His music is always good, warm, sincere, like the man who created it, for which reason it has something — indeed a great deal — to say to us all today.

Krenek, E. (1966). Exploring music; essays. New York: October House. (33-34)

Bolding by me. When I first read the beginning of this passage, I thought Krenek was going to use it as a take down on Milhaud, comparing the French composer’s home-design tastes to his music. Alas, such a wish for some drama-queen like language did not manifest.

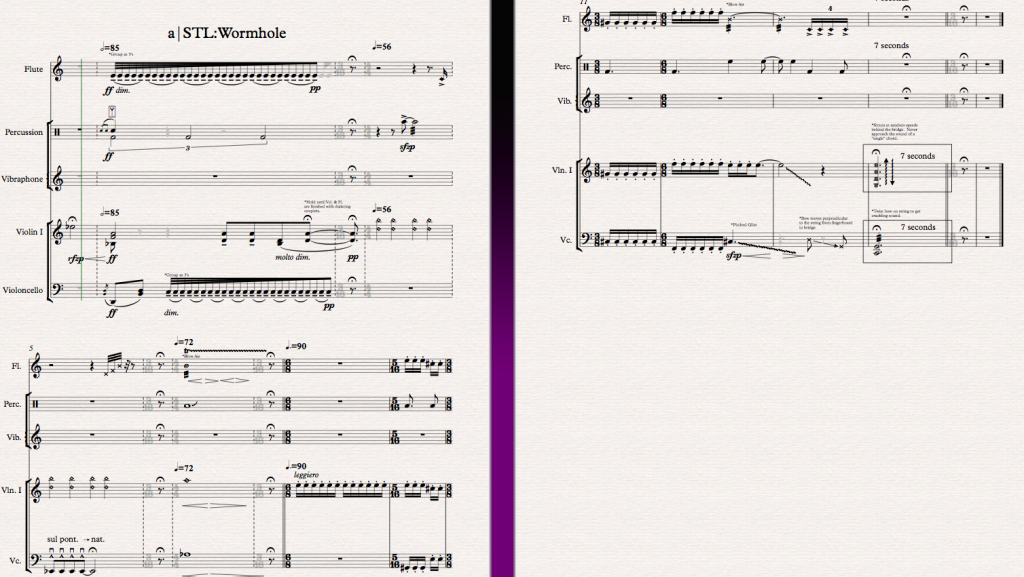

I wrote up a bit on the piece I’m writing for Cadillac Moon Ensemble’s new blog. Head over there to check it out and keep checking in over the next two weeks to read about the collaboration between CME and the other composers in Circles and Lines! Here’s an excerpt from the post:

Canis Major for Cadillac Moon Ensemble

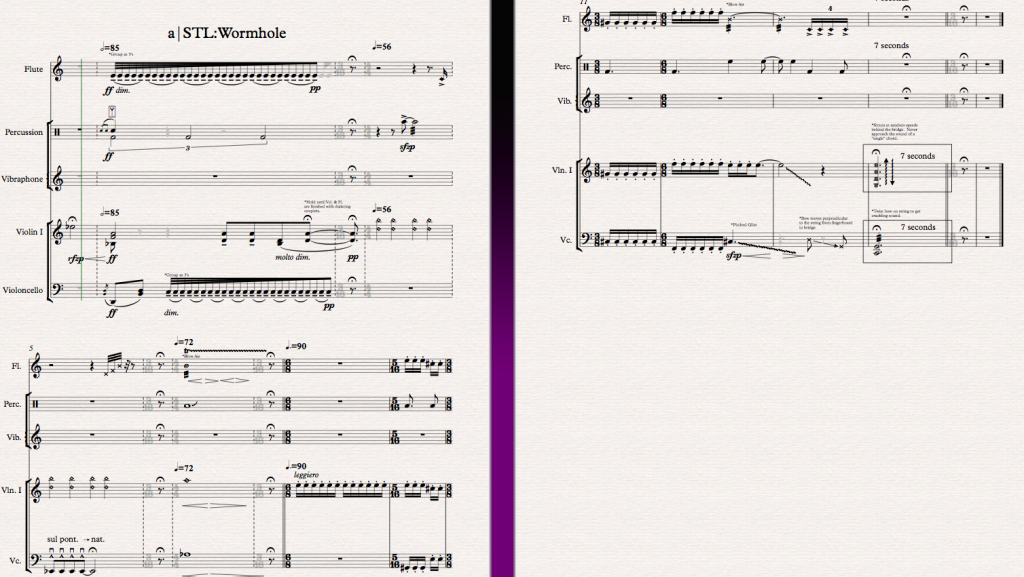

Canis Major is a piece for Flute, Violin, Cello and Percussion that I am writing for the wonderful people in Cadillac Moon Ensemble. The work is based around different astronomical bodies that partly make up the constellation that gives the piece its title. It is made up of five movements, three primary ‘location’ movements which represent the main bulk of the work, and two ‘traveling’ movements, based around slower than light and faster than light travel.

The titles of each movement are:

• I. Wolf-Rayet Star EZ CMa

• a. STL: Wormhole

• II. IC2177

• b. FTL Quantum Tunnel

• III. Sirius

Let me start off this post by noting that Krenek was a very smart man, but lived in a period where in much of Western Democracy, the right for women to vote was limited for much of his youth (In Switzerland for more than half his life!), and that feminist ideas had not wholly penetrated the West. That being said, some of the dynamics between male and female leads in his opera highlight a male dominated world and a view that is seated inside it. In Stewart’s biography on Krenek he notes Karl Kraus’ influence on Krenek’s view on women,

“The emotional essence of woman is not wanton or nihilistic, but rather is a tender fantasy which serves as the unconcious orgin of all that has any worth in human experience. herein lies the source of all inspriation and creativity…Reason must be supplied with proper goals from the outside; it must be given direction of a moral or aesthetic type. The feminine fantasy fecundates the moral reason and gives it that direction…The feminine is the source of all that is civilizing in society.”

Stewart, J. L. (1991). Ernst Krenek: The man and his music. Berkeley: University of California Press. (335)

This is not as wholly offensive as the idea of The Eternal Feminine, or Ewig-weibliche as espoused by Otto Weinenger in Sex and Character, which Kraus was responding to in formulating his ideas on the female’s essence,

“Woman is neither high-minded not low-minded, strong minded or weak-minded. She is the opposite of all these. Mind cannot be predicated of her at all; she is mindless. That however does not imply weakmindedness in the ordinary sense of the word, the absence of capacity to “get her bearings” in ordinary, everyday life…Woman is engrossed exclusively by sexuality, not intermittently, but throughout her life…The idea of pairing is the only conception which has positive worth for women.”

Weininger, O. (1906). Sex & character. London: W. Heinemann.

That being said, according to Sterwart, Krenek did indeed agree with Kraus’ idea of Ewig-weibliche in that it is,

“The mysterious centre of man’s nature – but it is also the purest expression of the orignal divine principle, undisguised essence, the primal order before the fall, the real likeness of God. This automatically puts the male world of wanting and doing into a dialectical relationship with this Ur-nature [that of the eternal feminine]; it becomes the central principle of the Fall, of ambiguous thought and intellectualism, which must be paid for with punishment and repentance. The repentance produces the creative principle of male organization demonstrated most clearly in the act of artistic construction.”

Krenek, E. (1966). Exploring music; essays. New York: October House. (116)

You can see the Krenek’s contrasting ideas of female and male essence clearly in Jonny Spielt Auf’s representation of the character Max, who is prone to brooding and being overly intellectual and his romantic interest, Anita who becomes a sort of muse to Max. Further on in Krenek’s essay on Berg’s Lulu he states the dialectical relationship more clearly,

“When the nightingale, speaking for the bird-world in Kraus’ poem,¹ says ‘you have the law, we have the world’, it voices an opposition of the most profound kind between the pre-logical sphere which is the real domain of the female nature, and the sphere of law which is thoroughly dominated, with inexorable logic, by language and the norms of art.”

[1. Text of Kraus poem below the fold.]

Krenek, E. (1966). Exploring music; essays. New York: October House. (117)

Although it’s wonderful to think of the idea of the female nature as inspiring, the “real likeness of God,” and “all that is civilizing in society”, the ideas engage in an incredible amount of “gender Orientalism”. What I mean by this is that it otherizes an entire gender. Indeed, coursing through the language of Krenek and Kraus, we have them calling female nature “pre-logical”, and outside reason, while representing the male nature as one of “wanting and doing”, and “Reason”. Orientalism as described by Edward Said uses the exact same kind of implicit dichotomy, even along the same lines of “rationality”, but instead of between the male and female genders, it is West vs. East.

« Continue reading “Gender Roles and Krenek” »

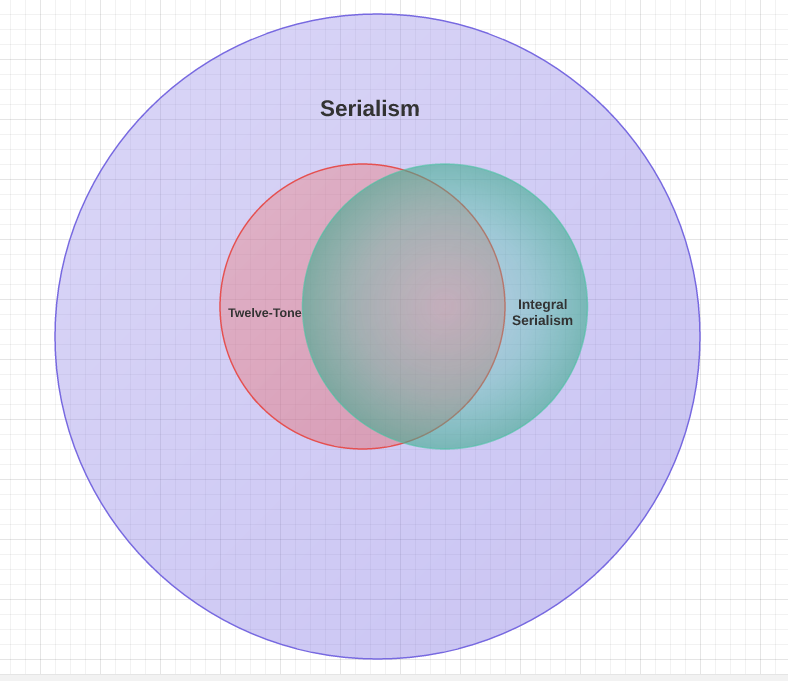

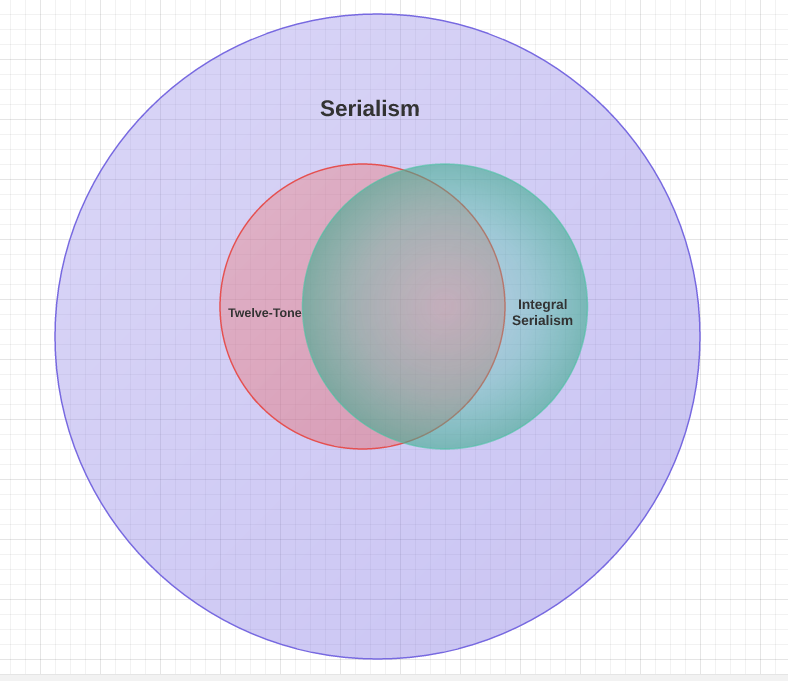

While reading more and more of this Krenek Biography, I came across a foot note that spoke a bit about the definitions of serialism and how Krenek used the term:

“Serialism” is often used to designate the twelve-tone technique, in which case the term “total serialism” or “integral serialism” refers to the technique in whichall the elements are treated serially. In his writings on the subject0, however, Krenek never uses “serialism” for the twelve-tone technique; he uses it only where others would use “total serialism” or “integral serialism.” The author has chosen to follow his example. In this account, therefore, “serialism” always refers to the later, more elaborate technique.

Stewart, J. L. (1991). Ernst Krenek: The man and his music. Berkeley: University of California Press. (269)

This is a huge problem with discussions of serialism. Many people tend to use serialism interchangeably with the twelve-tone technique, which is quite silly (and Stewart did it right here!). There are serial works that do not necessarily arrange their pitches through the twelve-tone technique. Not only that, but there are serial pieces that do not necessarily worry about arranging order to the pitches in a progressive fashion! Because of this, one could theoretically write a totally serial work without ever using the twelve-tone technique.

So to be clear. Twelve-Tone Music is a subset of serial music. Integral/Total Serialism is a subset of Serial music. The three overlap quite a bit, but are not the same thing.

Picture above so you don’t have to use your imagination.

I am doing a transcription of some of Krenek’s papers in preparation for a paper I am writing on his Solo Viola Sonata. Below are some of the notes from the work I’m doing and an excerpt from the beginning of the transcription (I am not sure whether I am allowed to post it all.)

Transcriber’s Notes:

Below is a transcription of 3 pages of analysis that were written by Ernst Krenek in preparation for a lecture that was broadcast by KPFA in Berkeley, CA in August of 1957. The analysis is on Krenek’s own Sonata for Solo Viola, op. 92/3 (1942), which is published by Universal Edition.

In this transcription I have tried to leave everything as Krenek wrote it, down to the punctuation. This transcription is mainly for ease of reading for future researchers as Krenek’s handwriting can be more difficult to read at some points.

I have also included images of the examples that Krenek cites, in some cases where he refers to a tone row in a piece, I have included the row and the excerpt of the row in its musical context.

Eric Lemmon, 2/2/2013

Notes for KPFA, Aug. 1957

Krenek Music, Berkeley

The Sonata for Viola solo was written in August 1942 at Bear Lake in the Rocky Mountains National Park of Colorado. In that time I was interested in adapting the twelve – tone technique, that I had studied and employed for more than twelve years, to the purposes of a type of structural design which was derived from the traditional concept of the sonata form.

The Sonata is based on two different twelve – tone rows which are constantly brought into variegated interplay until in the last movement they are integrated with each other. From the viewpoint of dodecaphonic procedure the treatment of the tone – rows may be called “free” in that the order of succession of the tones is occasionally modified in order to satisfy both the demands of the structural concept of the piece as well as the intention of gradually revealing the internal kinship of the two tone – rows which originally seem to be quite different from each other.

If anyone is interested in the works of Krenek, the Krenek Archive in Austria is an invaluable resource and many of the composer’s documents that were originally scattered about the US and Europe twenty years ago are being consolidated there. The staff are also incredibly helpful.

To this end he proposed a theory of music not confined to any idiom but embracing all musical phenomena and based on five premises, several of which had long been fundamental to his thought:

- Musical content does not represent anything extramusical.

- Musical thoughts cannot be rendered in any other medium. The creation of music involves thinking directly in musical language, which cannot be grasped directly in conceptual terms. Thus, for example, a composer thinks in terms of triads, dominant sevenths, and so on, and not in terms of things for which the music “stands” or “means.”

- Music is autonomous. It obeys its own laws. It is to be valued for itself and not for what it “expresses” historically, psychologically, or in any other way.

- The “laws” of music are not preordained, not “given in nature” and discovered there by man. Just as the axioms of geometry are free assumptions of the human intelligence for the purpose of geometric thought, so these laws are assumptions for the purpose of musical organization, for the articulation in tonal language of musical thought processes.

- Major-minor tonality is but one set of assumptions. Others, equally valid and effective, are possible. One such is the twelve-tone technique.

…

Still, one feels that in some degree this really was a paper amusement, the more so as it was followed by some extravagent analogies and claims for contemporary music. Starting with the instructive comparison of the so-called laws of music with the axioms of Euclidean geometry, which he rightly said were simply postulates to enable one to think in certain ways, he got carried away and asserted that the twelve-tone technique was like non-Euclidean geometry and yielded results similar to those produced when this geometry was applied in physics. Retrogression in twelve-tone music, he maintained, abolished ordinary time much as the concept of the fourth dimension does…”A musical retrogression could well create the impression of time moving backward.”

Stewart, J. L. (1991). Ernst Krenek: The man and his music. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bolding by me. Compare that last statement with some of the assumptions Krenek made about “musical phenomena”, specifically numbers 1 and 3. Stewart duly notes in his biography that it’s silly to think of a retrograde row as giving an impression of time moving backwards (after all, we just hear the music continuing forward as sound in time as listeners). But I find it more interesting that the example Krenek provided (and I bolded) directly conflicts with his strident claims about Music’s identity.

As someone who writes a lot, I sympathize with Krenek a bit, it’s hard to be entirely consistent all the time and especially hard to not say stupid stuff. Take this, and this for example.

|

Musicians

My Projects

|