I bought a recording of Cage’s Sonatas and Interludes to do some research on piano preparation. I have to say that the works are thoroughly enjoyable. The colors afforded to Cage (by himself) are really interesting and aesthetically pleasing. Regardless of my drooling over the work, am I just making this up or is the early soundtrack to this game really similar to Cage’s Sonatas XIV and XV?

|

|||

|

Simply put: String Quartet No. 1 – Movement II; Grave

String Quartet No. 1 – II. Grave The Cure at Troy

The Cure at Troy; I – Philoctetes The Cure at Troy; II – Neoptolomus’ Pity The Cure at Troy III – Philoctetes’ Venom If you would like scores to these works, send me an email!

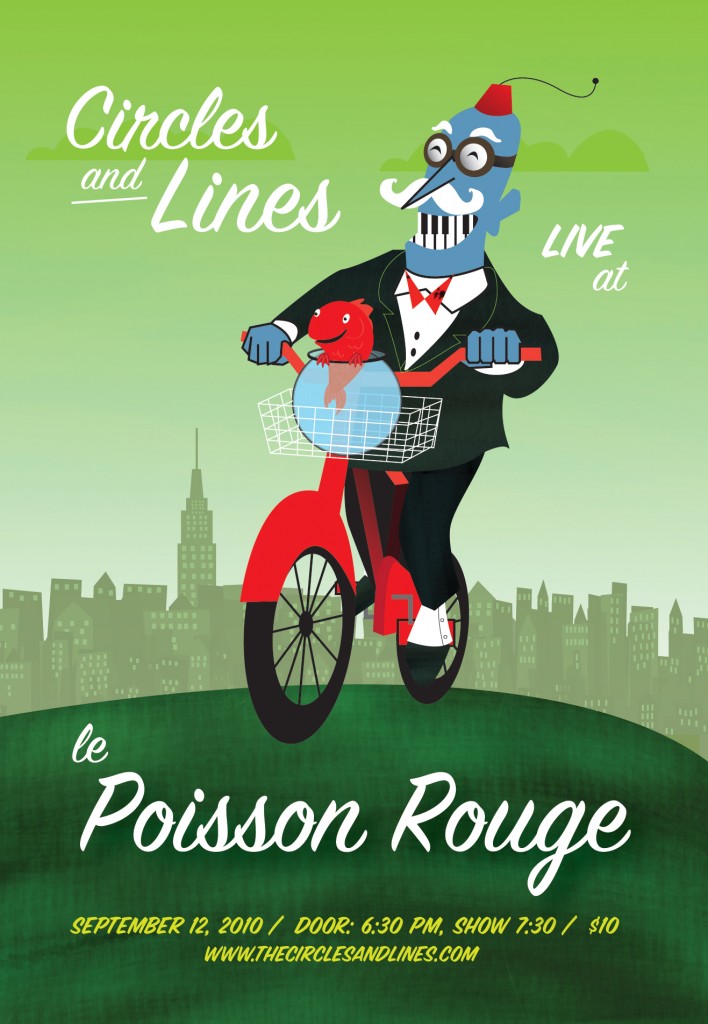

This means come see the premiere of my piece for flute and prepared piano, Little Respite! Le Poisson Rouge hosts a unique chamber music program featuring young up-and-coming composers Angelica Negron, Noam Faingold, Conrad Winslow, Eric Lemmon and Dylan Glatthorn on Sunday, September 12th, 2010 at 7:30 pm. The program includes world premieres by Winslow, Lemmon and Glatthorn and will also feature works by guest composers Pedro da Silva and Lucia Caruso. The group’s music draws from a wide range of influences including ambient/electronica, rock, tango, minimalism and traditional classical. Circles and Lines is a new composers consortium dedicated to providing an eclectic and accessible sample of compositional styles in contemporary classical music. The group has had featured programs at the alternative classical venue, Le Poisson Rouge and Greenwich House auditorium all in the heart of Greenwich village and have collaborated with Transit new music, Iktus percussion ensemble, and members of the Jack Quartet and Syzygy collective. Le Poisson Rouge is located on 158 Bleecker st. Subway: A, B, C, D, E, F and V trains to W. 4th St. station, R, W to 8th St. station, #6 to Astor Place station, #1 to Christopher St./Sheridan Sq. station. Tickets are $10 for all ages, made available the night of the performance, or in advance through Le Poisson Rouge’s website: I’ve recently been geeking out over a book (really it’s the appendix of a book) that has all practical flute multi-phonics written out. Yes, that’s correct 1826 different multi-phonics. The interesting thing about this appendix is that it is hyper specific to the actual frequencies of each pitch, dividing the scale used (from a fundamental pitch, say C, to an octave above) into 31 different tones. It also gives a conversion table to users who want to use the pitches in our typical 12 tone division. Why am I geeking out over this book? Well my next composition is a piece for Flute and (lightly) Prepared Piano. In a sense, this work is a study in how to apply extended techniques, which I have used from very sparingly to not at all. The piano’s preparation is sparse in that I apply a few mutes to the piano strings to shift the pitch outlaid on the piano up two octaves and a major third. Essentially, the goal is to get the dampened, glass color change that harmonics give. The other preparation is throwing some keys (the kind used to unlock doors) onto the lowest note on the piano, A1, so that when it’s played, we get a jarring, metallic buzz. The work is shaping up to be frenetic and crazed, which is exactly what I’m going for. My current struggle involves figuring out what multi-phonics will have ample tone production to be usable if the piano is simultaneously revving along like clockwork. Check out the first use of multi-phonics in flutes ever in Berio’s Sequenza and then listen to some even wilder music with Robert Dick playing: This past Thursday I was invited to go see Cadillac Moon Ensemble (CME) perform by two colleagues of mine, Evelyn Farny and Patti Kilroy. Opening up for them was Magic Names Group, a troupe of six vocalists founded specifically to perform the work Stimmung, which they performed in excerpt that evening. They also performed a work written by one of the members, Dafna Naftali, called “Panda Half-Life”, to which I unfortunately arrived at the end of. This post isn’t about CME or Magic Names Group though, but about how different works by the same composer can completely challenge your views on their compositional worth. I wrote earlier this year about my extreme economic (and partly philosophical/aesthetic) quarrel with Stockhausen’s Helicopter Music. Having heard some of his other music, I had come to generalize his work as being typical Darmstadt stuff. Fortunately, I’m constantly slapped in the face by the reality of an individual piece’s merits, so that my prejudices against a composer don’t stay for long. Though Magic Names Group only performed part of the work, the general effect and structure of the piece was apparent to me regardless of what I know about it before hand. Here’s what Wikipedia says about the work:

The beginning drones in the lowest two male voices (The Bass and Tenor II) started off on the fundamental pitch (Bb) and the two voices would shape their mouths in different vowel forms to alter the timbre of the pitch. These vowel alterations are what create the pitch changes that we hear in the aggregate sound of the overtone series. The droning in the beginning of the work reminded me of Buddhist chanting and as it flowed into different “Moments” it shifted to the sound of a Pérotin Organum. As I listened without the referential context of the work (which you can find here), I imagined that each moment was a veritable imitative tour of the world’s religious music. This is likely because of the in-depth use of overtone series, droning and rhythmic structure of the changing timbres. The music was enchantingly bizarre, and I’m glad I got to hear it. My piece, The Cure at Troy, which was premiered last year at Le Poisson Rouge is being performed at the Figment festival from June 11th through 13th at 11:00 AM. The piece is being performed in their lovely, totally recyclable, outdoor stage. http://figmentproject.org/2010/ Here’s some of the stuff they had last year: They claim to get about 40,000 people out, so it should be a lot of fun to play for the very early crowd. I love watching these two guys conduct, they are entirely hilarious to watch for different reasons, Strauss for the consistently blasé look on his face and Kleiber for the way he dances and gesticulates on stage, especially in his videos of pops concerts. Take a look:

The composer consortium I am a part of is having another concert at Le Poisson Rouge on May 2nd at 7:30 PM! It would be great to see you all there. Below is the program. We have some fantastic players joining us, including Iktus Percussion Quartet and Transit New Music Ensemble. Buy your tickets HERE! Prelude No. 26 for Solo Piano by Eric Lemmon La Aldea by Angélica Negrón Tango Variations for Double Bass Duo by Noam Faingold String Quartet No. 1 by Eric Lemmon Bonaparte Born to Party by Noam Faingold **Intermission** Count to Five by Angelica Negron I Could Dissolve into Sunlight by Conrad Winslow Fantasy for 171st St. by Dylan Glatthorn It’s Mutual by Conrad Winslow I first heard one of Berio’s works when a Trombonist was auditioning for the head of the Brass department position at NYU. He played the Sequenza V for that instrument but unfortunately didn’t wear the clown suit as the piece instructs. The technical prowess required to perform the trombone piece is entirely apparent from the beginning and only becomes increasingly so as Berio asks the player to emit multiphonics. Below is the Sequenza III for voice, sung with incredible facility by johanne saunier. I can’t say I terribly appreciate the piece (or many of Berio’s for that matter) except on a fundamental level, where the range of sounds emanating from the instrument (in this case the voice) is so varied and creative that one can appreciate what’s happening as a sort of pseudo-aesthetic object. I use pseudo and I should put “scare” quotes around aesthetic object, because Berio has certainly created the sound space around the singer’s babbling and clicks. Heideggerians would argue that this art, and I think I agree with this, but it’s a different kind of music from the kind that most of us consume which is driven towards expressing or setting an emotion. Take a Listen: Though I don’t believe that music education’s short shrift in curriculum alone is the reason for the past decades marked decline in the Classical audience base, it always deserves pointing out that music education isn’t just about introducing younger folks to traditional art music. In The Sunday New York Times Joanne Lipman contributed an Op-Ed that rehashed an anecdote about a concert for her recently passed high school music educator, Mr. K:

I have railed before about how cutting arts education is becoming and ongoing theme in public schools around the country since the passage of the NCLB Act, but the case I made in that instance was not as basic as the one Ms. Lipman is making. Music is about communication, it’s about sharing and emoting. Having an educator who understands this and can impart it is invaluable to human enrichment, this enrichment extends far beyond the formative years of youth. Losing education programs that could have as much impact on Ms. Lipman’s life as Mr. K’s did, not only deprives children of all the advantages I mentioned in previous articles, (better academics being one) but it also hampers cultural integration into society, ostensibly one of the two most important goals in education along with the learning of productive skills. |

Musicians

My Projects |

||