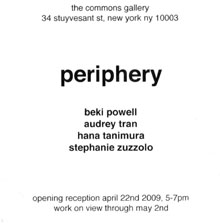

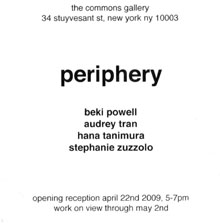

I recently went to Audrey Tran’s senior Art Thesis named Periphery and I talked to her about her piece which were essentially rows of saw grass arranged to be aesthetically pleasing and interesting to the eyes. She mentioned that the idea behind it is the grass growing in the cracks of the pavement. Now there are a slew of things that this evokes. For one, it reminds the viewer of the magnificent glory of nature even in it’s smallest offspring. Additionally it tells of the wily tenacity organic creatures and plants have, which strive to live and compete. Finally, and probably most starkly, this idea tells us of the transience of humanity’s impact on nature. Though we may be able to alter the climate of the planet, punch holes in the ozone and cause the greatest extinction level event since the dinosaurs were wiped from the planet, our planet will adjust, and it will do so without us. After we are gone, our steel will rust, our monuments crumble. Saw grass will poke through our concrete in no time at all. I recently went to Audrey Tran’s senior Art Thesis named Periphery and I talked to her about her piece which were essentially rows of saw grass arranged to be aesthetically pleasing and interesting to the eyes. She mentioned that the idea behind it is the grass growing in the cracks of the pavement. Now there are a slew of things that this evokes. For one, it reminds the viewer of the magnificent glory of nature even in it’s smallest offspring. Additionally it tells of the wily tenacity organic creatures and plants have, which strive to live and compete. Finally, and probably most starkly, this idea tells us of the transience of humanity’s impact on nature. Though we may be able to alter the climate of the planet, punch holes in the ozone and cause the greatest extinction level event since the dinosaurs were wiped from the planet, our planet will adjust, and it will do so without us. After we are gone, our steel will rust, our monuments crumble. Saw grass will poke through our concrete in no time at all.

In Audrey’s blog she covers lots of interesting pieces, which are indicative of (at least in some parts of our culture) an eco-conscious movement. Why is it that music has not caught on to this? I think for one, there is a certain element that appreciation for nature has already been explored by earlier musicians, whether it be Beethoven, Berlioz or Schumann and their works that are specifically referential to pastoral scenes. On the other hand, romantic painters (and writers) in the Americas also had a phase of depicting gorgeous landscapes (how is today’s eco-art different from that?). It is possible that because of the musical world’s inherent conservatism that we aren’t on the cutting edge. Despite these things, I refuse to believe our medium cannot be expressive in an eco-friendly manner. I think the problem possibly lies in the difference between today’s eco-conscious movement and yesteryear’s nature appreciators.

The Romantics viewed nature in awe (the work of God), and to a certain extent these landscapes seemed immutable to them. They believed that there was no way humanity could even pock mark these sweeping scenes, it was beyond our means to affect. Today, with our new consciousness of wide ranging human impact on the earth whether it be global warming or mountain-top removal mining, this admiration borne out of the aesthetic and immutability of nature holds no ground. Instead, current eco-conscious art is borne out of the desire to be a good steward of the earth and protect the beauty that is left, partly out of admiration for the aesthetics but also out of the need for self-preservation. Visual art (like always) is leading the charge in this artistic movement and there seems to be no response from music at all. The Romantics viewed nature in awe (the work of God), and to a certain extent these landscapes seemed immutable to them. They believed that there was no way humanity could even pock mark these sweeping scenes, it was beyond our means to affect. Today, with our new consciousness of wide ranging human impact on the earth whether it be global warming or mountain-top removal mining, this admiration borne out of the aesthetic and immutability of nature holds no ground. Instead, current eco-conscious art is borne out of the desire to be a good steward of the earth and protect the beauty that is left, partly out of admiration for the aesthetics but also out of the need for self-preservation. Visual art (like always) is leading the charge in this artistic movement and there seems to be no response from music at all.

I wrote the first movement of a viola concerto my junior year and each movement is supposed to evoke the feeling of being in a certain wondrous environment. I wanted the piece to represent how it felt to be in those places, rather than sound painting. This is where the trouble of being distinctly pro-environment in music lies. Without become obscurely referential (like writing satirical music based on the jingle of an environmentally offensive corporation) it becomes difficult to move beyond being simply admiring of nature, much like the pastoral romantics.

Maybe this isn’t such a bad thing, though, as being evocative of the feeling of say, The Red Woods of Yosemite (that is the subtitle to the first movement of my viola concerto) can help remind the audience the value of our single green-blue dot and all the places on it that we treasure.

I wrote yesterday about how Lady GaGa’s persona is essentially an imitation, philosophically and stylistically of Andy Warhol, even though the artists expressed themselves through different medium. At the end I made a broad conclusion that, as a culture, we are failing to move beyond Post-Modernism. I thought that I should explain more about why this -considering what we are going through ontologically- feels different with the advent of the digital age.

John Cage wrote very different music from Philip Glass, though both are post-modern composers What is Post-Modernism after all? I think it is important to define these parameters while we explore why we are just moving into a new period of the same thing. Wikipedia’s article (quite like most tracts on Post-Modernism) struggles to define the period in clear cut terms. This is because this period featured an extreme breakdown of unified cultural movements. Instead of one broad cultural movement, with everyone expressing themselves in a similar manner (like Romanticism) we had a bunch of splintered movements, where groups of artists or even individuals created art of cultural significance entirely different from what another group may be doing.

From the Wikipedia Page: “The Compact Oxford English Dictionary refers to postmodernism as ‘a style and concept in the arts characterized by distrust of theories and ideologies and by the drawing of attention to conventions.'” We can see in much of Andy Warhol’s work that his whole schtick with pop-art was drawing attention to conventions of our consumption. His famous Campbell Soup Can piece highlights the forms of a simple every day object, our convention of eating canned soup. Likewise, when John Cage wrote 4:33, he composed a work that, though he stated was intended to force people to listen to what was around them actually brought attention to the convention of a concert setting. Audience members attending the work for the first time probably thought, “I paid good money to hear music, why has the pianist not begun to play!”

This definition works well, but it fails to tell us the definitive features that are common in all post-modern works. Maybe this is impossible, but I think that we can still find prevalent cultural trends even in a movement that “distrusts theories and ideologies.” The Standford Encylopedia of Philosophy has a long article that delves deeply into what the editors believe are important philosophical tenants of post-modernism, but I thought I would refer to just one of the sections to keep this a blog post as opposed to a doctoral thesis on culture.

In the article Hyperreality is discussed:

Hyperreality is closely related to the concept of the simulacrum: a copy or image without reference to an original. In postmodernism, hyperreality is the result of the technological mediation of experience, where what passes for reality is a network of images and signs without an external referent, such that what is represented is representation itself.

Now, it is important to stop before continuing and note that consumerism, especially in industrialized nations since World War II, has been one of the defining cultural movements in the post-modern period. The before the Internet period (especially before our slick new social networking, web 2.0 apps) was defined by consumption of objects. The idea in America was that to obtain a white picket fenced house in the suburb, buy a car and TV was what every family needed to be happy. This hasn’t particularly been supplanted since the advent of the compu-global-hyper-mega-net, but in some ways, it is in the background as we are now consuming information from and about each other

Consider the fact that in many industrialized nations over 10% of the population have a Facebook profile. In Iceland 46.89%(!) of the population has a Facebook profile. Last January, 1 in 4 Americans had a Myspace account. It is clear that webmasters have a huge amount to gain in profit from our consumption of each other. What happens in these short profiles about us, or in stream-of-consciousness-like “tweets” is we create of projection of ourselves based on what we would like other people to know, very much akin to a brief meeting and conversation with a stranger.

This distillation of the self is essentially a Hyperreality of people. When I read a person’s profile, it does not permit me to know them intimately as I would through working with, or befriending an individual. All I merely consume from that profile is the copy or image that the creator would like me to see, without reference to the true individual, their flaws, their dreams, their greatest accomplishments or their lowest low. Their being is not their profile, which is merely a simplified reflection on an electronic surface.

This is why our society has not moved beyond post-modernism and why, I believe we are ontologically stuck artistically with no direction. It would be wonderful for someone or something to come along and shake that up.

Today’s pop music, and more generally; pop culture, fashion, etc. seems to be a huge throw back to the 80’s and subsequently the late 60’s early 70’s. That pop-cultural history gets reinvented should be no surprise as being steeped in our ontological past is just part of being human. Think about the recent popularization of extremely colorful and ostentatious fashions that hark back to the 80s and early 90s after the relatively plain late nineties, early 2000’s. Highlighting all of the current trend’s connections with past cultural periods would take forever, but I thought it would be interesting to note how still steeped in post-modernism our culture is, even though we seem to be in a certain transitional period. I am exploring one example out of a topic that would really need to be a book about cultural cycles.

Lady GaGa certainly takes her stylistic and artistic philosophy from the realm of Pop-Art, as an electronic-dance-disco artist, this is self evident as the style is essentially about glamorization. Though Mr. Warhol sought to highlight objects we use in everyday life (think Campell Soup Cans), there was a certain unintended consequence of glamorizing consumer objects, whether they be Marilyn Monroe or Coke. This is where the two connect, absurd glamorization of a certain desired objects.

In Lady GaGa’s case her music in her current two singles, Poker Face and Just Dance glamorize by hyper-sexualization of herself and glorifying a lifestyle, which includes: Being so drunk that one is mentally impaired (“I’ve had a little bit too much,” is the first line in Just Dance), Brief indecent exposure (“How’d I turn my shirt inside out,” in Just Dance) and a love life where transience of lovers is the norm (“I won’t tell you that I love you, Kiss or hug you, Cause I’m bluffin’ with my muffin,” In Poker Face). The sultry and heavy electronica that is played along with the content of the lyrics reminds of house parties in Williamburg, Brooklyn. Indeed, the set of the video for Just Dance is a house party. As an aside, it wouldn’t be surprising is she has attended a Brooklyn loft party, as she is native of Yonkers and grew up on the Upper West Side. Combine these elements of her music with her sparkled out fashion, huge sunglasses, face paint and dresses which are further out there than Björk’s swan and we have ourself a reflection of Warholian ideas.

I am not the first one to notice or write about this connection. The New Yorker’s review of Lady Gaga quotes Warhol as one of her influences, “Less verifiable is her theorizing about her work. She cites Andy Warhol, claims to be a ‘fame Robin Hood’ who has lost her mind”. Additionally, watching her aloof, bizarre responses to questions from talk show hosts seems to be a page taken straight from Warhol:

BBC interview (1981)

Edward Smith: Would you like to see your pictures on as many walls as possible, then?

Andy Warhol: Uh, no, I like them in closets.

What does this mean? I believe that looking at current trends in pop-culture, and our entire culture’s inability to move beyond the heavy consumerism that defined Post-Modernism, that we are just cycling into another phase of the same thing. I’m going to go out on a limb here, and say this is a bad thing. It’s time to kill Post-Modernism and move on to something new.

I wrote part of this piece at the end of last year. It, like the last movement of my Viola Sonata, is in a semetrical mode consisting of the pitches, C, Db, Eb, E, F#, G#, A# (Bb). I feel it is very different from most of what I have written before, though still considerably conservative in sound as the clusters I use are more effects than part of the specific harmonic texture. I feel that it is different because the affect of the work is considerably darker than all of the other works I have written. I have my own reasons why this may be, but instead of forcing my intentions down your throat, I’ll let you glean your own meaning from the work.

As I said earlier, I wrote part of it several months ago, let it sit for a while and then completed it earlier this month. Thus, it is clearly in a two part form, with the second part, nearly identical to the first excluding the re-transitional and coda material. The difference between the parts essentially is I’ve turned the grave eighth notes section in the second system and later on used those pitches in the extremely fast runs of 64th notes.

Enjoy the part below the break!

« Continue reading “Prelude in Bb Minor” »

More standard violin rep. Sonata 3 on Wikipedia

Two of these or Russian editions. If anyone has western editions throw them up on IMSLP and shoot me a link.

« Continue reading “Brahms Violin Sonatas” »

I don’t know these works at all (being a violist, this should make sense, since I never play violin + cello music) so I am quoting an article from Classical Archives

Schumann composed three trios for violin, cello and piano: in D minor, Op. 63; in F major, Op. 80 (both from 1847); and in G minor, Op. 110 (1851). The first of these, in D minor, is generally regarded as the strongest work of the three. An experimental approach to harmony in the F major Trio is usually given as a weakness when the piece measured against its Classical-era models, while the G minor Trio shows some signs of the decay that accompanied the composer’s encroaching mental illness. The intimate chamber music genres allowed Schumann to indulge his preference for intricate figurations and subtle harmonic inflections that are such a salient feature of his solo piano pieces. Not surprisingly, the piano chamber works are clearly piano driven, with the strings either following the keyboard part or acting in opposition to it as a unified block.

Music is below the break.

« Continue reading “Schumann Piano Trios” »

Fauré’s Piano + string works are here. Youtube recordings will be listed soon!

« Continue reading “Fauré’s String Works Part 2” »

Fauré is known for his flowing melodies and lucid harmonies. Listening to his music it is logical to assume he is the precursor to french impressionistic music which his later works often strayed towards. When you hear other composers stereotyping “french” music they often get something that is imitative of Fauré’s music, delicate but not necessarily fragile. The next splurge I put out on Fauré’s works will include his much more frequently played chamber works. Below the fold are his violin and cello sonatas and several short piece for violin or cello and piano. If I can find some recordings of these works on Youtube I’ll update this post later today.

Updated With Recordings!

« Continue reading “Fauré’s String Works Part 1” »

The Brahms Cello Sonatas are part of the standard cello repertoire (duh!). I’ll post the score along with what Wikipedia has to say about the works.

« Continue reading “Brahms Cello Sonatas” »

I just got finished playing an awesome work by my good friend Dylan Glatthorn. Dylan is a native of St. Petersburg, Florida and a fellow senior at New York University with me. He is the winner of the Alan Menken Scholarship here and I believe he has been working on the musical since he’s been here at NYU. I played some of the music last year when it was beginning to take shape at his Junior recital and was called again to play at his backer’s audition just yesterday.

« Continue reading “Republic The Musical” »

|

Musicians

My Projects

|

I recently went to Audrey Tran’s senior Art Thesis named Periphery and I talked to her about her piece which were essentially rows of saw grass arranged to be aesthetically pleasing and interesting to the eyes. She mentioned that the idea behind it is the grass growing in the cracks of the pavement. Now there are a slew of things that this evokes. For one, it reminds the viewer of the magnificent glory of nature even in it’s smallest offspring. Additionally it tells of the wily tenacity organic creatures and plants have, which strive to live and compete. Finally, and probably most starkly, this idea tells us of the transience of humanity’s impact on nature. Though we may be able to alter the climate of the planet, punch holes in the ozone and cause the greatest extinction level event since the dinosaurs were wiped from the planet, our planet will adjust, and it will do so without us. After we are gone, our steel will rust, our monuments crumble. Saw grass will poke through our concrete in no time at all.

I recently went to Audrey Tran’s senior Art Thesis named Periphery and I talked to her about her piece which were essentially rows of saw grass arranged to be aesthetically pleasing and interesting to the eyes. She mentioned that the idea behind it is the grass growing in the cracks of the pavement. Now there are a slew of things that this evokes. For one, it reminds the viewer of the magnificent glory of nature even in it’s smallest offspring. Additionally it tells of the wily tenacity organic creatures and plants have, which strive to live and compete. Finally, and probably most starkly, this idea tells us of the transience of humanity’s impact on nature. Though we may be able to alter the climate of the planet, punch holes in the ozone and cause the greatest extinction level event since the dinosaurs were wiped from the planet, our planet will adjust, and it will do so without us. After we are gone, our steel will rust, our monuments crumble. Saw grass will poke through our concrete in no time at all. The Romantics viewed nature in awe (the work of God), and to a certain extent these landscapes seemed immutable to them. They believed that there was no way humanity could even pock mark these sweeping scenes, it was beyond our means to affect. Today, with our new consciousness of wide ranging human impact on the earth whether it be global warming or mountain-top removal mining, this admiration borne out of the aesthetic and immutability of nature holds no ground. Instead, current eco-conscious art is borne out of the desire to be a good steward of the earth and protect the beauty that is left, partly out of admiration for the aesthetics but also out of the need for self-preservation. Visual art (like always) is leading the charge in this artistic movement and there seems to be no response from music at all.

The Romantics viewed nature in awe (the work of God), and to a certain extent these landscapes seemed immutable to them. They believed that there was no way humanity could even pock mark these sweeping scenes, it was beyond our means to affect. Today, with our new consciousness of wide ranging human impact on the earth whether it be global warming or mountain-top removal mining, this admiration borne out of the aesthetic and immutability of nature holds no ground. Instead, current eco-conscious art is borne out of the desire to be a good steward of the earth and protect the beauty that is left, partly out of admiration for the aesthetics but also out of the need for self-preservation. Visual art (like always) is leading the charge in this artistic movement and there seems to be no response from music at all.